Videos/A Digital Media Primer For Geeks

Wiki edition

This first video from Xiph.Org presents the technical foundations of modern digital media via a half-hour firehose of information. One community member called it "a Uni lecture I never got but really wanted."

The program offers a brief history of digital media, a quick summary of the sampling theorem, and myriad details of low level audio and video characterization and formatting. It's intended for budding geeks looking to get into video coding, as well as the technically curious who want to know more about the media they wrangle for work or play.

Players supporting WEBM: VLC 1.1+, Firefox 4 (beta), Chrome (development versions), Opera, more…

Players supporting Ogg/Theora: VLC, Firefox, Opera, more…

If you're having trouble with playback in a modern browser or player, please visit our playback troubleshooting and discussion page.

Introduction

Workstations and high-end personal computers have been able to manipulate digital audio pretty easily for about fifteen years now. It's only been about five years that a decent workstation's been able to handle raw video without a lot of expensive special purpose hardware.

But today even most cheap home PCs have the processor power and storage necessary to really toss raw video around, at least without too much of a struggle. So now that everyone has all of this cheap media-capable hardware, more people, not surprisingly, want to do interesting things with digital media, especially streaming. YouTube was the first huge success, and now everybody wants in.

Well good! Because this stuff is a lot of fun!

It's no problem finding consumers for digital media. But here I'd

like to address the engineers, the mathematicians, the hackers, the

people who are interested in discovering and making things and

building the technology itself. The people after my own heart.

Digital media, compression especially, is perceived to be super-elite, somehow incredibly more difficult than anything else in computer science. The big industry players in the field don't mind this perception at all; it helps justify the staggering number of very basic patents they hold. They like the image that their media researchers "are the best of the best, so much smarter than anyone else that their brilliant ideas can't even be understood by mere mortals." This is bunk.

Digital audio and video and streaming and compression offer endless deep and stimulating mental challenges, just like any other discipline. It seems elite because so few people have been involved. So few people have been involved perhaps because so few people could afford the expensive, special-purpose equipment it required. But today, just about anyone watching this video has a cheap, general-purpose computer powerful enough to play with the big boys. There are battles going on today around HTML5 and browsers and video and open vs. closed. So now is a pretty good time to get involved. The easiest place to start is probably understanding the technology we have right now.

This is an introduction. Since it's an introduction, it glosses over a ton of details so that the big picture's a little easier to see. Quite a few people watching are going to be way past anything that I'm talking about, at least for now. On the other hand, I'm probably going to go too fast for folks who really are are brand new to all of this, so if this is all new, relax. The important thing is to pick out any ideas that really grab your imagination. Especially pay attention to the terminology surrounding those ideas, because with those, and Google, and Wikipedia, you can dig as deep as interests you.

So, without any further ado, welcome to one hell of a new hobby.

Going deeper…

- About Xiph.Org: Why you should care about open media

- HTML5 Video and H.264: what history tells us and why we're standing with the web: Chris Blizzard of Mozilla on free formats and the open web

- Dive into HTML5: tutorial on HTML5 web video

- Chat with the creators of the video via freenode IRC in #xiph.

Analog vs Digital

Sound is the propagation of pressure waves through air, spreading out

from a source like ripples spread from a stone tossed into a pond. A

microphone, or the human ear for that matter, transforms these passing

ripples of pressure into an electric signal. Right, this is

middle school science class, everyone remembers this. Moving on.

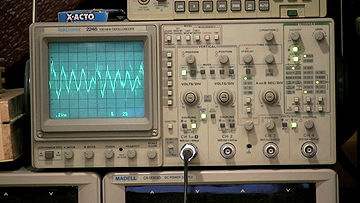

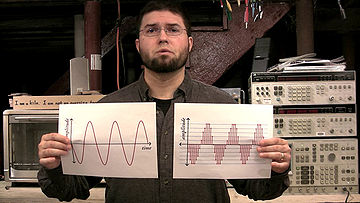

That audio signal is a one-dimensional function, a single value varying over time. If we slow the 'scope down a bit... that should be a little easier to see. A few other aspects of the signal are important. It's continuous in both value and time; that is, at any given time it can have any real value, and there's a smoothly varying value at every point in in time. No matter how much we zoom in, there are no discontinuities, no singularities, no instantaneous steps or points where the signal ceases to exist. It's defined everywhere. Classic continuous math works very well on these signals.

A digital signal on the other hand is discrete in both value and time. In the simplest and most common system, called Pulse Code Modulation, one of a fixed number of possible values directly represents the instantaneous signal amplitude at points in time spaced a fixed distance apart. The end result is a stream of digits.

Now this looks an awful lot like this. It seems intuitive that we should somehow be able to rigorously transform one into the other, and good news, the Sampling Theorem says we can and tells us how. Published in its most recognizable form by Claude Shannon in 1949 and built on the work of Nyquist, and Hartley, and tons of others, the sampling theorem states that not only can we go back and forth between analog and digital, but also lays down a set of conditions for which conversion is lossless and the two representations become equivalent and interchangeable. When the lossless conditions aren't met, the sampling theorem tells us how and how much information is lost or corrupted.

Up until very recently, analog technology was the basis for practically everything done with audio, and that's not because most audio comes from an originally analog source. You may also think that since computers are fairly recent, analog signal technology must have come first. Nope. Digital is actually older. The telegraph predates the telephone by half a century and was already fully mechanically automated by the 1860s, sending coded, multiplexed digital signals long distances. You know... tickertape. Harry Nyquist of Bell Labs was researching telegraph pulse transmission when he published his description of what later became known as the Nyquist frequency, the core concept of the sampling theorem. Now, it's true the telegraph was transmitting symbolic information, text, not a digitized analog signal, but with the advent of the telephone and radio, analog and digital signal technology progressed rapidly and side-by-side.

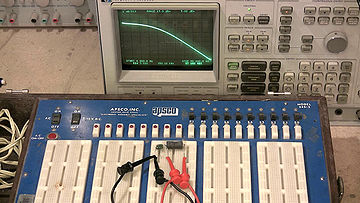

Audio had always been manipulated as an analog signal because... well, gee, it's so much easier. A second-order low-pass filter, for example, requires two passive components. An all-analog short-time Fourier transform, a few hundred. Well, maybe a thousand if you want to build something really fancy (bang on the 3585). Processing signals digitally requires millions to billions of transistors running at microwave frequencies, support hardware at very least to digitize and reconstruct the analog signals, a complete software ecosystem for programming and controlling that billion-transistor juggernaut, digital storage just in case you want to keep any of those bits for later...

So we come to the conclusion that analog is the only practical way to do much with audio... well, unless you happen to have a billion transistors and all the other things just lying around. And since we do, digital signal processing becomes very attractive.

For one thing, analog componentry just doesn't have the flexibility of a general purpose computer. Adding a new function to this beast [the 3585]... yeah, it's probably not going to happen. On a digital processor though, just write a new program. Software isn't trivial, but it is a lot easier.

Perhaps more importantly though every analog component is an approximation. There's no such thing as a perfect transistor, or a perfect inductor, or a perfect capacitor. In analog, every component adds noise and distortion, usually not very much, but it adds up. Just transmitting an analog signal, especially over long distances, progressively, measurably, irretrievably corrupts it. Besides, all of those single-purpose analog components take up a lot of space. Two lines of code on the billion transistors back here can implement a filter that would require an inductor the size of a refrigerator.

Digital systems don't have these drawbacks. Digital signals can be stored, copied, manipulated, and transmitted without adding any noise or distortion. We do use lossy algorithms from time to time, but the only unavoidably non-ideal steps are digitization and reconstruction, where digital has to interface with all of that messy analog. Messy or not, modern conversion stages are very, very good. By the standards of our ears, we can consider them practically lossless as well.

With a little extra hardware, then, most of which is now small and inexpensive due to our modern industrial infrastructure, digital audio is the clear winner over analog. So let us then go about storing it, copying it, manipulating it, and transmitting it.

Going deeper…

- Wikipedia: Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem

- MIT OpenCourseWare Lecture notes from 6.003 signals and systems.

- Wikipedia: The history of analog filters such as the RC low-pass shown connected to the spectrum analyzer in the video.

Raw (digital audio) meat

Pulse Code Modulation is the most common representation for raw audio. Other practical representations do exist: for example, the Sigma-Delta coding used by the SACD, which is a form of Pulse Density Modulation. That said, Pulse Code Modulation is far and away dominant, mainly because it's so mathematically convenient. An audio engineer can spend an entire career without running into anything else.

PCM encoding can be characterized in three parameters, making it easy

to account for every possible PCM variant with mercifully little

hassle.

sample rate

The first parameter is the sampling rate. The highest frequency an encoding can represent is called the Nyquist Frequency. The Nyquist frequency of PCM happens to be exactly half the sampling rate. Therefore, the sampling rate directly determines the highest possible frequency in the digitized signal.

Analog telephone systems traditionally band-limited voice channels to just under 4kHz, so digital telephony and most classic voice applications use an 8kHz sampling rate: the minimum sampling rate necessary to capture the entire bandwidth of a 4kHz channel. This is what an 8kHz sampling rate sounds like—a bit muffled but perfectly intelligible for voice. This is the lowest sampling rate that's ever been used widely in practice.

From there, as power, and memory, and storage increased, consumer computer hardware went to offering 11, and then 16, and then 22, and then 32kHz sampling. With each increase in the sampling rate and the Nyquist frequency, it's obvious that the high end becomes a little clearer and the sound more natural.

The Compact Disc uses a 44.1kHz sampling rate, which is again slightly better than 32kHz, but the gains are becoming less distinct. 44.1kHz is a bit of an oddball choice, especially given that it hadn't been used for anything prior to the compact disc, but the huge success of the CD has made it a common rate.

The most common hi-fidelity sampling rate aside from the CD is 48kHz. There's virtually no audible difference between the two. This video, or at least the original version of it, was shot and produced with 48kHz audio, which happens to be the original standard for high-fidelity audio with video.

Super-hi-fidelity sampling rates of 88, and 96, and 192kHz have also appeared. The reason for the sampling rates beyond 48kHz isn't to extend the audible high frequencies further. It's for a different reason.

Stepping back for just a second, the French mathematician Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier showed that we can also think of signals like audio as a set of component frequencies. This frequency-domain representation is equivalent to the time representation; the signal is exactly the same, we're just looking at it a different way. Here we see the frequency-domain representation of a hypothetical analog signal we intend to digitally sample.

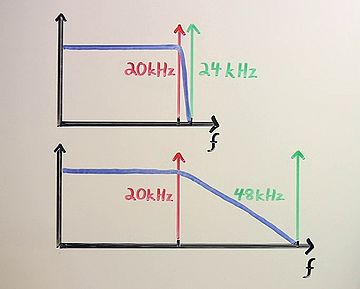

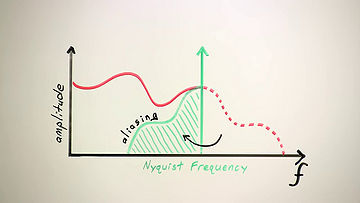

The sampling theorem tells us two essential things about the sampling process. First, that a digital signal can't represent any frequencies above the Nyquist frequency. Second, and this is the new part, if we don't remove those frequencies with a low-pass filter before sampling, the sampling process will fold them down into the representable frequency range as aliasing distortion.

Aliasing, in a nutshell, sounds freakin' awful, so it's essential to remove any beyond-Nyquist frequencies before sampling and after reconstruction.

Human frequency perception is considered to extend to about 20kHz. In

44.1 or 48kHz sampling, the low pass before the sampling stage has to

be extremely sharp to avoid cutting any audible frequencies below

20kHz but still not allow frequencies above the Nyquist to leak

forward into the sampling process. This is a difficult filter to

build, and no practical filter succeeds completely. If the sampling

rate is 96kHz or 192kHz on the other hand, the low pass has an extra

octave or two for its transition band. This is a much easier filter to

build. Sampling rates beyond 48kHz are actually one of those messy

analog stage compromises.

sample format

The second fundamental PCM parameter is the sample format; that is, the format of each digital number. A number is a number, but a number can be represented in bits a number of different ways.

Early PCM was eight-bit linear, encoded as an unsigned byte. The dynamic range is limited to about 50dB and the quantization noise, as you can hear, is pretty severe. Eight-bit audio is vanishingly rare today.

Digital telephony typically uses one of two related non-linear eight bit encodings called A-law and μ-law. These formats encode a roughly 14 bit dynamic range into eight bits by spacing the higher amplitude values farther apart. A-law and mu-law obviously improve quantization noise compared to linear 8-bit, and voice harmonics especially hide the remaining quantization noise well. All three eight-bit encodings, linear, A-law, and mu-law, are typically paired with an 8kHz sampling rate, though I'm demonstrating them here at 48kHz.

Most modern PCM uses 16- or 24-bit two's-complement signed integers to encode the range from negative infinity to zero decibels in 16 or 24 bits of precision. The maximum absolute value corresponds to zero decibels. As with all the sample formats so far, signals beyond zero decibels, and thus beyond the maximum representable range, are clipped.

In mixing and mastering, it's not unusual to use floating-point numbers for PCM instead of integers. A 32 bit IEEE754 float, that's the normal kind of floating point you see on current computers, has 24 bits of resolution, but a seven bit floating-point exponent increases the representable range. Floating point usually represents zero decibels as +/-1.0, and because floats can obviously represent considerably beyond that, temporarily exceeding zero decibels during the mixing process doesn't cause clipping. Floating-point PCM takes up more space, so it tends to be used only as an intermediate production format.

Lastly, most general purpose computers still read and

write data in octet bytes, so it's important to remember that samples

bigger than eight bits can be in big- or little-endian order, and both

endiannesses are common. For example, Microsoft WAV files are little-endian,

and Apple AIFC files tend to be big-endian. Be aware of it.

channels

The third PCM parameter is the number of channels. The convention in

raw PCM is to encode multiple channels by interleaving the samples of

each channel together into a single stream. Straightforward and extensible.

done!

And that's it! That describes every PCM representation ever. Done. Digital audio is so easy! There's more to do of course, but at this point we've got a nice useful chunk of audio data, so let's get some video too.

Going deeper…

- Wikipedia's article on filter roll-off, to learn why it's hard to build analog filters with a very narrow transition band between the passband and the stopband. Filters that achieve such hard edges often do so at the expense of increased ripple and phase distortion.

- Some more minutiae about PCM in practice.

- DPCM and ADPCM, simple audio codecs loosely inspired by PCM.

Video vegetables (they're good for you!)

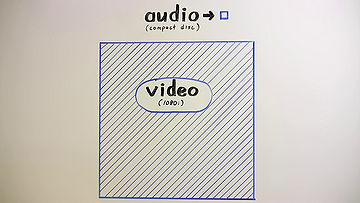

One could think of video as being like audio but with two additional spatial dimensions, X and Y, in addition to the dimension of time. This is mathematically sound. The Sampling Theorem applies to all three video dimensions just as it does the single time dimension of audio.

Audio and video are obviously quite different in practice. For one, compared to audio, video is huge. Raw CD audio is about 1.4 megabits per second. Raw 1080i HD video is over 700 megabits per second. That's more than 500 times more data to capture, process, and store per second. By Moore's law... that's... let's see... roughly eight doublings times two years, so yeah, computers requiring about an extra fifteen years to handle raw video after getting raw audio down pat was about right.

Basic raw video is also just more complex than basic raw audio. The sheer volume of data currently necessitates a representation more efficient than the linear PCM used for audio. In addition, electronic video comes almost entirely from broadcast television alone, and the standards committees that govern broadcast video have always been very concerned with backward compatibility. Up until just last year in the US, a sixty-year-old black and white television could still show a normal analog television broadcast. That's actually a really neat trick.

The downside to backward compatibility is that once a detail makes it into a standard, you can't ever really throw it out again. Electronic video has never started over from scratch the way audio has multiple times. Sixty years worth of clever but obsolete hacks necessitated by the passing technology of a given era have built up into quite a pile, and because digital standards also come from broadcast television, all these eldritch hacks have been brought forward into the digital standards as well.

In short, there are a whole lot more details involved in digital video

than there were with audio. There's no hope of covering them

all completely here, so we'll cover the broad fundamentals.

resolution and aspect

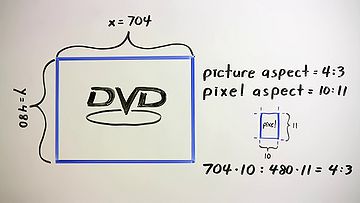

The most obvious raw video parameters are the width and height of the picture in pixels. As simple as that may sound, the pixel dimensions alone don't actually specify the absolute width and height of the picture, as most broadcast-derived video doesn't use square pixels. The number of scanlines in a broadcast image was fixed, but the effective number of horizontal pixels was a function of channel bandwidth. Effective horizontal resolution could result in pixels that were either narrower or wider than the spacing between scanlines.

Standards have generally specified that digitally sampled video should

reflect the real resolution of the original analog source, so a large

amount of digital video also uses non-square pixels. For example, a

normal 4:3 aspect NTSC DVD is typically encoded with a display

resolution of 704 by 480, a ratio wider than 4:3. In this case, the

pixels themselves are assigned an aspect ratio of 10:11, making them

taller than they are wide and narrowing the image horizontally to the

correct aspect. Such an image has to be resampled to show properly on

a digital display with square pixels.

frame rate and interlacing

The second obvious video parameter is the frame rate, the number of full frames per second. Several standard frame rates are in active use. Digital video, in one form or another, can use all of them. Or, any other frame rate. Or even variable rates where the frame rate changes adaptively over the course of the video. The higher the frame rate, the smoother the motion and that brings us, unfortunately, to interlacing.

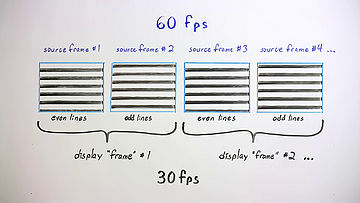

In the very earliest days of broadcast video, engineers sought the

fastest practical frame rate to smooth motion and to minimize flicker

on phosphor-based CRTs. They were also under pressure to use the

least possible bandwidth for the highest resolution and fastest frame

rate. Their solution was to interlace the video where the even lines

are sent in one pass and the odd lines in the next. Each pass is

called a field and two fields sort of produce one complete frame.

"Sort of", because the even and odd fields aren't actually from the

same source frame. In a 60 field per second picture, the source frame

rate is actually 60 full frames per second, and half of each frame,

every other line, is simply discarded. This is why we can't

deinterlace a video simply by combining two fields into one frame;

they're not actually from one frame to begin with.

gamma

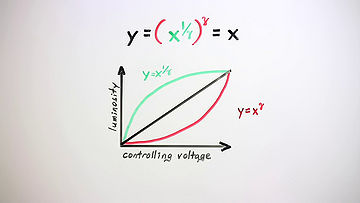

The cathode ray tube was the only available display technology for most of the history of electronic video. A CRT's output brightness is nonlinear, approximately equal to the input controlling voltage raised to the 2.5th power. This exponent, 2.5, is designated gamma, and so it's often referred to as the gamma of a display. Cameras, though, are linear, and if you feed a CRT a linear input signal, it looks a bit like this.

As there were originally to be very few cameras, which were fantastically expensive anyway, and hopefully many, many television sets which best be as inexpensive as possible, engineers decided to add the necessary gamma correction circuitry to the cameras rather than the sets. Video transmitted over the airwaves would thus have a nonlinear intensity using the inverse of the set's gamma exponent, so that once a camera's signal was finally displayed on the CRT, the overall response of the system from camera to set was back to linear again.

Almost.

There were also two other tweaks. A television camera actually uses a gamma exponent that's the inverse of 2.2, not 2.5. That's just a correction for viewing in a dim environment. Also, the exponential curve transitions to a linear ramp near black. That's just an old hack for suppressing sensor noise in the camera.

Gamma correction also had a lucky benefit. It just so happens that the

human eye has a perceptual gamma of about 3. This is relatively close

to the CRT's gamma of 2.5. An image using gamma correction devotes

more resolution to lower intensities, where the eye happens to have

its finest intensity discrimination, and therefore uses the available

scale resolution more efficiently. Although CRTs are currently

vanishing, a standard sRGB computer display still uses a nonlinear

intensity curve similar to television, with a linear ramp near black,

followed by an exponential curve with a gamma exponent of 2.4. This

encodes a sixteen bit linear range down into eight bits.

color and colorspace

The human eye has three apparent color channels, red, green, and blue, and most displays use these three colors as additive primaries to produce a full range of color output. The primary pigments in printing are Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow for the same reason; pigments are subtractive, and each of these pigments subtracts one pure color from reflected light. Cyan subtracts red, magenta subtracts green, and yellow subtracts blue.

Video can be, and sometimes is, represented with red, green, and blue color channels, but RGB video is atypical. The human eye is far more sensitive to luminosity than it is the color, and RGB tends to spread the energy of an image across all three color channels. That is, the red plane looks like a red version of the original picture, the green plane looks like a green version of the original picture, and the blue plane looks like a blue version of the original picture. Black and white times three. Not efficient.

For those reasons and because, oh hey, television just happened to start out as black and white anyway, video usually is represented as a high resolution luma channel—the black & white—along with additional, often lower resolution chroma channels, the color. The luma channel, Y, is produced by weighting and then adding the separate red, green and blue signals. The chroma channels U and V are then produced by subtracting the luma signal from blue and the luma signal from red.

When YUV is scaled, offset, and quantized for digital video, it's

usually more correctly called Y'CbCr, but the more generic term YUV is

widely used to describe all the analog and digital variants of this

color model.

chroma subsampling

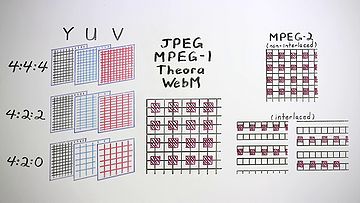

The U and V chroma channels can have the same resolution as the Y channel, but because the human eye has far less spatial color resolution than spatial luminosity resolution, chroma resolution is usually halved or even quartered in the horizontal direction, the vertical direction, or both, usually without any significant impact on the apparent raw image quality. Practically every possible subsampling variant has been used at one time or another, but the common choices today are 4:4:4 video, which isn't actually subsampled at all, 4:2:2 video in which the horizontal resolution of the U and V channels is halved, and most common of all, 4:2:0 video in which both the horizontal and vertical resolutions of the chroma channels are halved, resulting in U and V planes that are each one quarter the size of Y.

The terms 4:2:2, 4:2:0, 4:1:1, and so on and so forth, aren't complete descriptions of a chroma subsampling. There's multiple possible ways to position the chroma pixels relative to luma, and again, several variants are in active use for each subsampling. For example, motion JPEG, MPEG-1 video, MPEG-2 video, DV, Theora, and WebM all use or can use 4:2:0 subsampling, but they site the chroma pixels three different ways.

Motion JPEG, MPEG-1 video, Theora and WebM all site chroma pixels between luma pixels both horizontally and vertically.

MPEG-2 sites chroma pixels between lines, but horizontally aligned with every other luma pixel. Interlaced modes complicate things somewhat, resulting in a siting arrangement that's a tad bizarre.

And finally PAL-DV, which is always interlaced, places the chroma pixels in the same position as every other luma pixel in the horizontal direction, and vertically alternates chroma channel on each line.

That's just 4:2:0 video. I'll leave the other subsamplings as homework for the

viewer. Got the basic idea, moving on.

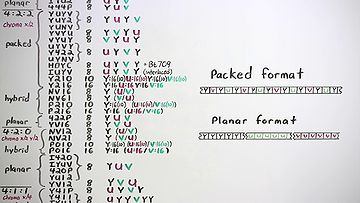

pixel formats

In audio, we always represent multiple channels in a PCM stream by interleaving the samples from each channel in order. Video uses both packed formats that interleave the color channels, as well as planar formats that keep the pixels from each channel together in separate planes stacked in order in the frame. There are at least 50 different formats in these two broad categories with possibly ten or fifteen in common use.

Each chroma subsampling and different bit-depth requires a different packing arrangement, and so a different pixel format. For a given unique subsampling, there are usually also several equivalent formats that consist of trivial channel order rearrangements or repackings, due either to convenience once-upon-a-time on some particular piece of hardware, or sometimes just good old-fashioned spite.

Pixels formats are described by a unique name or fourcc code. There

are quite a few of these and there's no sense going over each one now.

Google is your friend. Be aware that fourcc codes for raw video

specify the pixel arrangement and chroma subsampling, but generally

don't imply anything certain about chroma siting or color space. YV12

video to pick one, can use JPEG, MPEG-2 or DV chroma siting, and any

one of several YUV colorspace definitions.

done!

That wraps up our not-so-quick and yet very incomplete tour of raw video. The good news is we can already get quite a lot of real work done using that overview. In plenty of situations, a frame of video data is a frame of video data. The details matter, greatly, when it come time to write software, but for now I am satisfied that the esteemed viewer is broadly aware of the relevant issues.

Going deeper…

- The y4m format is the most common simple container for raw YUV video. People occasionally use OggYUV to store it in Ogg instead.

- Learn about high dynamic range imaging, which achieves better representation of the full range of brightnesses in the real world by using more than 8 bits per channel.

- Learn about how trichromatic color vision works in humans, and how human color perception is encoded in the CIE 1931 XYZ color space.

- Compare with the Lab color space, mathematically equivalent but structured to account for "perceptual uniformity".

- If we were all dichromats then video would only need two color channels. Some humans might be tetrachromats, in which case they would need an additional color channel for video to fully represent their vision.

- Test your color vision (or at least your monitor).

- YCbCr is defined in terms of RGB by the ITU in two incompatible standards: Rec. 601 and Rec. 709. Both conversion standards are lossy, which has prompted some to adopt a lossless alternative called YCoCg.

Containers

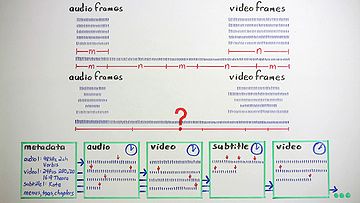

So. We have audio data. We have video data. What remains is the more familiar non-signal data and straight-up engineering that software developers are used to, and plenty of it.

Chunks of raw audio and video data have no externally-visible structure, but they're often uniformly sized. We could just string them together in a rigid predetermined ordering for streaming and storage, and some simple systems do approximately that. Compressed frames, though, aren't necessarily a predictable size, and we usually want some flexibility in using a range of different data types in streams. If we string random formless data together, we lose the boundaries that separate frames and don't necessarily know what data belongs to which streams. A stream needs some generalized structure to be generally useful.

In addition to our signal data, we also have our PCM and video parameters. There's probably plenty of other metadata we also want to deal with, like audio tags and video chapters and subtitles, all essential components of rich media. It makes sense to place this metadata—that is, data about the data—within the media itself.

Storing and structuring formless data and disparate metadata is the

job of a container. Containers provide framing for the data blobs,

interleave and identify multiple data streams, provide timing

information, and store the metadata necessary to parse, navigate,

manipulate, and present the media. In general, any container can hold

any kind of data. And data can be put into any container.

Credits

In the past thirty minutes, we've covered digital audio, video, some history, some math and a little engineering. We've barely scratched the surface, but it's time for a well-earned break.

There's so much more to talk about, so I hope you'll join me again in our next episode. Until then—Cheers!

Written by: Christopher (Monty) Montgomery and the Xiph.Org Community

Intro, title and credits music:

"Boo Boo Coming", by Joel Forrester

Performed by the Microscopic Septet

Used by permission of Cuneiform Records.

Original source track All Rights Reserved.

www.cuneiformrecords.com

This Video Was Produced Entirely With Free and Open Source Software:

GNU

Linux

Fedora

Cinelerra

The Gimp

Audacity

Postfish

Gstreamer

All trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Complete video CC-BY-NC-SA

Text transcript and Wiki edition CC-BY-SA

A Co-Production of Xiph.Org and Red Hat Inc.

(C) 2010, Some Rights Reserved