Videos/Digital Show and Tell: Difference between revisions

(→The Spectrum and Waveform Viewer: source boxes grey?) |

m (→Epilogue: link-text choice and grammar) |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[[Image:Xiph_ep02_test.png|400px|right]] | [[Image:Xiph_ep02_test.png|400px|right]] | ||

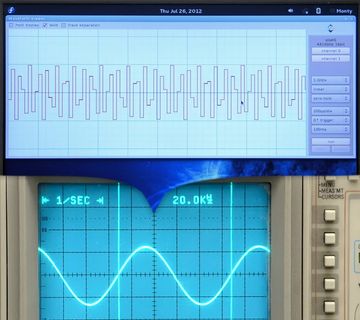

Hi, I'm Monty Montgomery from [http://www.redhat.com/ Red Hat] and [http://xiph.org/ Xiph.Org]. | “Hi, I'm Monty Montgomery from [http://www.redhat.com/ Red Hat] and [http://xiph.org/ Xiph.Org]. | ||

A few months ago, I wrote | “A few months ago, I wrote | ||

[http://people.xiph.org/~xiphmont/demo/neil-young.html an article on digital audio and why 24bit/192kHz music downloads don't make sense]. | [http://people.xiph.org/~xiphmont/demo/neil-young.html an article on digital audio and why 24bit/192kHz music downloads don't make sense]. | ||

In the article, I | In the article, I | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

[[WikiPedia:Digital-to-analog_converter|convert from digital back to analog]]. | [[WikiPedia:Digital-to-analog_converter|convert from digital back to analog]]. | ||

Of everything in the entire article, '''that''' was the number one thing | “Of everything in the entire article, '''that''' was the number one thing | ||

people wrote about. In fact, more than half the mail I got was questions and | people wrote about. In fact, more than half the mail I got was questions and | ||

comments about basic digital signal behavior. Since there's interest, let's | comments about basic digital signal behavior. Since there's interest, let's | ||

take a little time to play with some ''simple'' digital signals. | take a little time to play with some ''simple'' digital signals. ” | ||

==Veritas ex machina== | ==Veritas ex machina== | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

[[Image:Dsat_005.jpg|200px|right]] | [[Image:Dsat_005.jpg|200px|right]] | ||

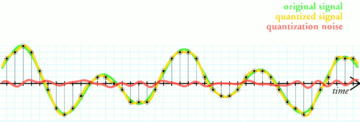

If we pretend for a moment that we have no idea how digital signals really | |||

behave | behave, then it doesn't make sense for us to use digital test | ||

equipment | equipment. Fortunately for this exercise, there's still plenty | ||

of working analog lab equipment out there. | of working analog lab equipment out there. | ||

We need a [[WikiPedia:Function_generator|signal generator]] to provide us with analog input | |||

signals--in this case, an | signals--in this case, an | ||

[http://www.home.agilent.com/en/pd-3325A%3Aepsg%3Apro-pn-3325A/synthesizer-function-generator?pm=PL&nid=-536900197.536896863&cc=SE&lc=swe HP3325] | [http://www.home.agilent.com/en/pd-3325A%3Aepsg%3Apro-pn-3325A/synthesizer-function-generator?pm=PL&nid=-536900197.536896863&cc=SE&lc=swe HP3325] | ||

from 1978 | from 1978. | ||

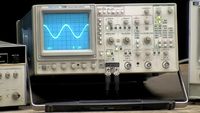

We'll observe our analog waveforms on [[WikiPedia:Oscilloscope_types#Cathode-ray_oscilloscope_.28CRO.29|analog oscilloscopes]], | |||

like this Tektronix 2246 from the mid-90s, one of the last and | like this Tektronix 2246 from the mid-90s, one of the last and best analog scopes made. | ||

Finally, we'll inspect the [[WikiPedia:Spectral_density#Electrical_engineering|frequency spectrum]] of our signals using an | |||

[[WikiPedia:Spectrum_analyzer#Swept-tuned|analog spectrum analyzer]], this | [[WikiPedia:Spectrum_analyzer#Swept-tuned|analog spectrum analyzer]], this | ||

[http://www.home.agilent.com/en/pd-3585A%3Aepsg%3Apro-pn-3585A/spectrum-analyzer-high-perf-20hz-40mhz?pm=PL&nid=-536900197.536897319&cc=SE&lc=swe HP3585] | [http://www.home.agilent.com/en/pd-3585A%3Aepsg%3Apro-pn-3585A/spectrum-analyzer-high-perf-20hz-40mhz?pm=PL&nid=-536900197.536897319&cc=SE&lc=swe HP3585] | ||

| Line 62: | Line 59: | ||

from input to what you see on the screen is completely analog. | from input to what you see on the screen is completely analog. | ||

All of this equipment is vintage, but | All of this equipment is vintage, but the specs are still quite good. | ||

We start with the signal generator set to output a 1 [[WikiPedia:Hertz#SI_multiples|kHz]] | |||

sine wave at one [[WikiPedia:Volt|Volt]] [[WikiPedia:Amplitude#Root_mean_square_amplitude|RMS]]. | sine wave at one [[WikiPedia:Volt|Volt]] [[WikiPedia:Amplitude#Root_mean_square_amplitude|RMS]]. | ||

We see the sine wave on the oscilloscope, can verify that it is indeed | We see the sine wave on the oscilloscope, can verify that it is indeed | ||

| Line 76: | Line 72: | ||

with the highest peak about 70[[WikiPedia:Decibel|dB]] or so below | with the highest peak about 70[[WikiPedia:Decibel|dB]] or so below | ||

[[WikiPedia:Fundamental_frequency|the fundamental]]. | [[WikiPedia:Fundamental_frequency|the fundamental]]. | ||

This doesn't matter to the demos, but it's good to take notice of it now to avoid confusion later. | |||

later | |||

For | For digital conversion, we use a boring, consumer-grade, eMagic USB1 | ||

audio device. It's | audio device. It's more than ten years old at this point, and it's | ||

getting obsolete. | getting obsolete. | ||

| Line 92: | Line 84: | ||

[[WikiPedia:Noise_floor|noise behavior]], | [[WikiPedia:Noise_floor|noise behavior]], | ||

[[WikiPedia:Digital-to-analog_converter#DAC_performance|everything]]... | [[WikiPedia:Digital-to-analog_converter#DAC_performance|everything]]... | ||

You may not | |||

have noticed. Just because we can measure an improvement doesn't | have noticed. Just because we can measure an improvement doesn't | ||

mean we can hear it, and even these old consumer boxes were already at | mean we can hear it, and even these old consumer boxes were already at | ||

| Line 102: | Line 94: | ||

re-conversion to analog and observation on the output scopes. | re-conversion to analog and observation on the output scopes. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Stairsteps== | ==Stairsteps== | ||

[[Image:Dsat 007.png|360px|right]] | |||

[[Image:Dsat 006.jpg|360px|right]] | [[Image:Dsat 006.jpg|360px|right]] | ||

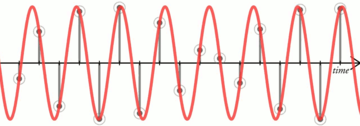

First demo: We begin by converting an analog signal to digital and | |||

then right back to analog again with no other steps. | |||

then right back to analog again with no other steps. | |||

The signal generator is set to produce a 1kHz sine wave just like | |||

before | before and we can see the analog sine wave on the input-side oscilloscope. The eMagic digitizes our signal to | ||

[[Videos/A_Digital_Media_Primer_For_Geeks#Raw_.28digital_audio.29_meat|16 bit PCM at 44.1kHz]], | [[Videos/A_Digital_Media_Primer_For_Geeks#Raw_.28digital_audio.29_meat|16 bit PCM at 44.1kHz]], | ||

same as on a CD. | same as on a CD. The spectrum of the digitized signal on the Thinkpad matches what we saw earlier and what we see now on the analog spectrum analyzer, aside from its | ||

[[WikiPedia:High_impedance|high-impedance input]] being just a smidge noisier. For now, the waveform display shows our digitized sine wave as a | |||

stairstep pattern, one step for each sample. | |||

[[WikiPedia:High_impedance|high-impedance input]] being just a smidge noisier. | |||

stairstep pattern, one step for each sample. | |||

When we look at the output signal that's been converted | |||

from digital back to analog, we see that it's exactly like the original sine wave. No stairsteps. | |||

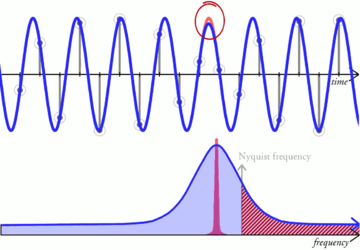

1 kHz is still a fairly low frequency, so perhaps the stairsteps are just | |||

hard to see or they're being smoothed away. Next, set the signal generator to 15kHz, which is much closer to [[WikiPedia:Nyquist_frequency|Nyquist]]. | |||

Now the sine wave is represented by less than three samples per cycle, and the digital waveform appears rather poor! Yet the analog output is still a perfect sine wave, exactly like the original. | |||

As we keep increasing frequency, all the way to 20kHz, the output waveform is still perfect. No jagged edges, no dropoff, no stairsteps. | |||

So where'd the stairsteps go? It's a trick question; they were never there. Drawing a digital waveform as a stairstep was wrong to begin with. | |||

A stairstep is a continuous-time function. It's jagged, and it's piecewise, but it has a defined value at every point in time. | |||

A sampled signal is entirely different. It's discrete-time; it's only got a value right at each instantaneous sample point and it's | |||

undefined, there is no value at all, everywhere between. A discrete-time signal is properly drawn as a lollipop graph. | |||

The continuous, analog counterpart of a digital signal passes smoothly through each sample point, and that's just as true for high | |||

frequencies as it is for low. | |||

[[Image:Dsat 008.png|360px|right]] | [[Image:Dsat 008.png|360px|right]] | ||

The interesting and non-obvious bit is that [[WikiPedia:Nyquist%E2%80%93Shannon_sampling_theorem|there's only one | |||

bandlimited signal that passes exactly through each sample point]]; it's a unique solution. If you sample a bandlimited signal and then convert it back, the original input is also the only possible output. | |||

A signal that differs even minutely from the original includes frequency content at or beyond Nyquist, breaks the bandlimiting requirement and isn't a valid solution. | |||

So how did everyone get confused and start thinking of digital signals as stairsteps? I can think of two good reasons. | |||

First: it's easy to convert a sampled signal to a true stairstep. Just | |||

extend each sample value forward until the next sample period. This is | extend each sample value forward until the next sample period. This is | ||

called a [[WikiPedia:Zero-order hold|zero-order hold]], and it's an important part of how some | called a [[WikiPedia:Zero-order hold|zero-order hold]], and it's an important part of how some | ||

digital-to-analog converters work, especially the simplest ones. | digital-to-analog converters work, especially the simplest ones. | ||

As a result, anyone who looks up [[WikiPedia:Digital-to-analog_converter#Practical_operation|digital-to-analog converter or | |||

digital-to-analog conversion]] is probably going to see a diagram of a | digital-to-analog conversion]] is probably going to see a diagram of a | ||

stairstep waveform somewhere, but that's not a finished conversion, | stairstep waveform somewhere, but that's not a finished conversion, | ||

and it's not the signal that comes out. | and it's not the signal that comes out. | ||

Second, and this is probably the more likely reason, engineers who | |||

supposedly know better, | supposedly know better (yes, even I) draw stairsteps even though they're | ||

technically wrong. It's a sort of | technically wrong. It's a sort of one-dimensional version of | ||

[[WikiPedia:MacPaint#Development|fat bits in an image editor]]. | [[WikiPedia:MacPaint#Development|fat bits in an image editor]]. | ||

Pixels aren't squares either, they're samples of a 2-dimensional | |||

function space and so they're also, conceptually, infinitely small | function space and so they're also, conceptually, infinitely small | ||

points. Practically, it's a real pain in the ass to see or manipulate | points. Practically, it's a real pain in the ass to see or manipulate | ||

infinitely small anything, so big squares it is. | infinitely small anything, so big squares it is. | ||

Digital stairstep drawings are exactly the same thing. It's just a convenient drawing. The stairsteps aren't really there. | |||

<div style="clear:both"></div> | |||

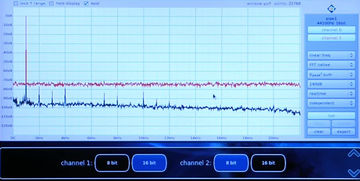

==Bit-depth== | ==Bit-depth== | ||

| Line 194: | Line 158: | ||

When we convert a digital signal back to analog, the result is | When we convert a digital signal back to analog, the result is | ||

''also'' smooth regardless of the [[WikiPedia:Audio_bit_depth|bit depth]]. 24 bits or 16 bits | ''also'' smooth regardless of the [[WikiPedia:Audio_bit_depth|bit depth]]. It doesn't matter if it's 24 bits or 16 bits or 8 bits. | ||

or 8 bits. | |||

So does that mean that the digital bit depth makes no difference at | So does that mean that the digital bit depth makes no difference at | ||

all? Of course not. | all? Of course not. | ||

Channel 2 | Channel 2 is the same sine wave input, but we quantize it with | ||

[[WikiPedia:Dither|dither]] down to 8 bits. | [[WikiPedia:Dither|dither]] down to 8 bits. | ||

On the scope, we still see a nice | On the scope, we still see a nice | ||

smooth sine wave on channel 2. Look very close, and you'll also see a | smooth sine wave on channel 2. Look very close, and you'll also see a | ||

bit more noise. That's a clue. | bit more noise. That's a clue. | ||

If we look at the spectrum of the signal | If we look at the spectrum of the signal, our sine wave is | ||

still there unaffected, but the noise level of the 8-bit signal on | still there unaffected, but the noise level of the 8-bit signal on | ||

the second channel is much higher | the second channel is much higher. And that's the difference, the only difference, the number of bits makes. | ||

And that's the difference the number of bits makes. | |||

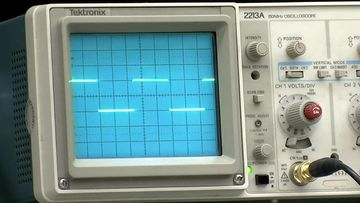

When we digitize a signal, first we sample it. The | When we digitize a signal, first we sample it. The | ||

sampling step is perfect; it loses nothing. But then we [[WikiPedia:Quantization_(sound_processing)|quantize]] it, | sampling step is perfect; it loses nothing. But then we [[WikiPedia:Quantization_(sound_processing)|quantize]] it, | ||

and [[WikiPedia:Quantization_error|quantization adds noise]]. | and [[WikiPedia:Quantization_error|quantization adds noise]]. | ||

The number of bits determines how much noise and so the level of the | The number of bits determines how much noise and so the level of the | ||

noise floor. | noise floor. | ||

What does this dithered quantization noise sound like? | What does this dithered quantization noise sound like? | ||

Those of you who have used analog recording equipment might think to yourselves, "My goodness! That sounds like tape hiss!" | |||

Those of you who have used analog recording equipment | |||

Well, it doesn't just sound like tape hiss, it acts like it too, and | Well, it doesn't just sound like tape hiss, it acts like it too, and | ||

if we use a [[WikiPedia:Dither#Different_types|gaussian dither]] then it's | if we use a [[WikiPedia:Dither#Different_types|gaussian dither]] then it's | ||

| Line 236: | Line 187: | ||

of [[WikiPedia:Magnetic_tape_sound_recording|magnetic audio tape]] | of [[WikiPedia:Magnetic_tape_sound_recording|magnetic audio tape]] | ||

in [[WikiPedia:Shannon–Hartley_theorem#Examples|bits instead of decibels]], in order to put things in a | in [[WikiPedia:Shannon–Hartley_theorem#Examples|bits instead of decibels]], in order to put things in a | ||

digital perspective. [[WikiPedia:Compact cassettes|Compact cassettes]] | digital perspective. [[WikiPedia:Compact cassettes|Compact cassettes]], for those of you who are old enough to remember them, could reach as | ||

deep as 9 bits in perfect conditions | deep as 9 bits in perfect conditions. 5 to 6 bits was | ||

more typical, especially if it was a recording made on a | more typical, especially if it was a recording made on a | ||

[[WikiPedia:Cassette_deck|tape deck]]. That's right | [[WikiPedia:Cassette_deck|tape deck]]. That's right; your old mix tapes were only about 6 bits | ||

deep | deep if you were lucky! | ||

The very best professional [[WikiPedia:Reel-to-reel_audio_tape_recording|open reel tape]] used in studios could barely | The very best professional [[WikiPedia:Reel-to-reel_audio_tape_recording|open reel tape]] used in studios could barely | ||

hit | hit 13 bits ''with'' [[WikiPedia:Reel-to-reel_audio_tape_recording#Noise_reduction|advanced noise reduction]]. | ||

That's why seeing '[[WikiPedia:SPARS_code|D D D]]' on a [[WikiPedia:Compact_disk|Compact Disc]] used to be such a big, | |||

high-end deal. | high-end deal. | ||

<div style="clear:both"></div> | |||

==Dither== | ==Dither== | ||

[[Image:Dsat_011.png|360px|right]] | [[Image:Dsat_011.png|360px|right]] | ||

We've been quantizing with [[Wikipedia:dither|dither]]. What is dither | |||

exactly and, more importantly, what does it do? | exactly and, more importantly, what does it do? | ||

The | The simplest way to quantize a signal is to choose the digital | ||

amplitude value closest to the original analog amplitude | amplitude value [[WikiPedia:Rounding|closest to the original analog amplitude]]. | ||

Unfortunately, the exact noise that results from this simple | |||

quantization scheme depends somewhat on the input signal | quantization scheme depends somewhat on the input signal. | ||

It may be inconsistent, cause distortion, or be | |||

undesirable in some other way. | undesirable in some other way. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

<center><div style="background-color:#DDDDFF;border-color:#CCCCDD;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | <center><div style="background-color:#DDDDFF;border-color:#CCCCDD;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | ||

'''Going deeper…''' | '''Going deeper…''' | ||

*Cameron Nicklaus Christou's thesis [http://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/10012/3867/1/thesis.pdf Optimal Dither and Noise Shaping in Image Processing] provides an ''excellent'' explanation of dither and noise shaping. | *Cameron Nicklaus Christou's thesis [http://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/10012/3867/1/thesis.pdf Optimal Dither and Noise Shaping in Image Processing] provides an ''excellent'' explanation of dither and noise shaping. | ||

</div></center> | </div> </center> | ||

Dither is specially-constructed noise that substitutes for the noise | Dither is specially-constructed noise that substitutes for the noise | ||

produced by simple quantization. Dither doesn't [[WikiPedia:Sound_masking|drown out or mask]] | produced by simple quantization. Dither doesn't [[WikiPedia:Sound_masking|drown out or mask]] | ||

quantization noise, it | quantization noise, it replaces it with noise characteristics | ||

of our choosing that aren't influenced by the input. | of our choosing that aren't influenced by the input. | ||

The signal generator has too much noise for this test so we produce a mathematically perfect sine wave with the ThinkPad and quantize it to 8 bits with dithering. | |||

We see the sine wave on waveform display and output scope, and | |||

We see | |||

a clean frequency peak with a uniform noise floor on both spectral displays | a clean frequency peak with a uniform noise floor on both spectral displays | ||

just like before. Again, this is with dither. | just like before. Again, this is with dither. | ||

| Line 279: | Line 231: | ||

Now I turn dithering off. | Now I turn dithering off. | ||

The quantization noise | The quantization noise that dither had spread out into a nice, flat noise | ||

floor, piles up into harmonic distortion peaks. The noise floor is | floor, piles up into harmonic distortion peaks. The noise floor is | ||

lower, but the level of distortion becomes nonzero, and the distortion | lower, but the level of distortion becomes nonzero, and the distortion | ||

| Line 286: | Line 238: | ||

At 8 bits this effect is exaggerated. At 16 bits, | At 8 bits this effect is exaggerated. At 16 bits, | ||

even without dither, harmonic distortion is going to be so low as to | even without dither, harmonic distortion is going to be so low as to | ||

be completely inaudible. | be completely inaudible. Still, we can use dither to eliminate it completely if we so choose. | ||

Still, we can use dither to eliminate it completely if we so choose. | |||

Turning the dither off again for a moment, you'll notice that the | Turning the dither off again for a moment, you'll notice that the | ||

| Line 297: | Line 247: | ||

In a sense, everything quantizing to zero is just 100% distortion! | In a sense, everything quantizing to zero is just 100% distortion! | ||

Dither eliminates this distortion too. | Dither eliminates this distortion too. When we reenable dither, we clearly see our signal at 1/4 bit with a nice flat noise floor. | ||

The noise floor doesn't have to be flat. Dither is noise of our | The noise floor doesn't have to be flat. Dither is noise of our | ||

choosing, so | choosing, so it makes sense to choose a noise as [http://www.acoustics.salford.ac.uk/res/cox/sound_quality/?content=subjective inoffensive] and | ||

[[WikiPedia:Absolute_threshold_of_hearing|difficult to notice]] | [[WikiPedia:Absolute_threshold_of_hearing|difficult to notice]] | ||

as possible. | as possible. | ||

Human hearing is [[WikiPedia:Equal-loudness_contour|most sensitive in the midrange from 2kHz to 4kHz]]; that's where background noise is going to be the most obvious. | |||

We can [[WikiPedia:Noise_shaping|shape dithering noise]] away from sensitive frequencies to where | We can [[WikiPedia:Noise_shaping|shape dithering noise]] away from sensitive frequencies to where | ||

hearing is less sensitive, usually the highest frequencies. | hearing is less sensitive, usually the highest frequencies. | ||

Lastly, dithered quantization noise ''is'' higher [[WikiPedia:Sound_power|power]] overall | Lastly, dithered quantization noise ''is'' higher [[WikiPedia:Sound_power|power]] overall | ||

than undithered quantization noise even | than undithered quantization noise, even though it often sounds quieter, and | ||

you can see that on a [[WikiPedia:VU_meter|VU meter]] during passages of near-silence. | you can see that on a [[WikiPedia:VU_meter|VU meter]] during passages of near-silence. However, | ||

dither isn't only an on or off choice. We can reduce the dither's | dither isn't only an on or off choice. We can reduce the dither's | ||

power to balance less noise against a bit of distortion to minimize | power to balance less noise against a bit of distortion to minimize | ||

the overall effect. | the overall effect. | ||

For the next test, we also [[WikiPedia:Amplitude_modulation|modulate the input signal]] like this to show how a varying input affects the quantization noise. At | |||

full dithering power, the noise is uniform, constant, and featureless | full dithering power, the noise is uniform, constant, and featureless | ||

just like we expect | just like we expect. | ||

As we reduce the dither's power, the input increasingly | As we reduce the dither's power, the input increasingly | ||

affects the amplitude and the character of the quantization noise. | affects the amplitude and the character of the quantization noise. | ||

Shaped dither behaves similarly, but noise shaping lends one more nice | Shaped dither behaves similarly, but noise shaping lends one more nice | ||

advantage | advantage; it can use a somewhat lower | ||

dither power before the input has as much effect on the output. | dither power before the input has as much effect on the output. | ||

Despite all | Despite all this text spent on dither, the differences exist 100 decibels or more below [[WikiPedia:Full_scale|full scale]]. If the CD had been | ||

differences | |||

[http://www.research.philips.com/technologies/projects/cd/index.html 14 bits as originally designed], | [http://www.research.philips.com/technologies/projects/cd/index.html 14 bits as originally designed], | ||

dither ''might'' be | perhaps dither ''might'' be | ||

more important | more important. At 16 bits it's mostly a wash. It's reasonable to treat | ||

dither as an insurance policy that gives several extra | |||

decibels of dynamic range just in case. | decibels of dynamic range just in case. That said no | ||

one ever ruined a great recording by not dithering the final master. | one ever ruined a great recording by not dithering the final master. | ||

==Bandlimitation and timing== | ==Bandlimitation and timing== | ||

[[image: | [[image:Dsat_016.jpg|360px|right]] | ||

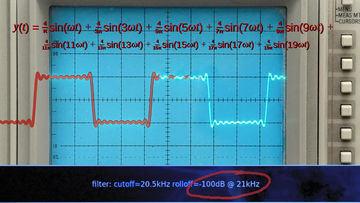

We've been using [[WikiPedia:Sine_wave|sine waves]]. They're the obvious choice when what we | We've been using [[WikiPedia:Sine_wave|sine waves]]. They're the obvious choice when what we | ||

want to see is a system's behavior at a given isolated frequency. Now | want to see is a system's behavior at a given isolated frequency. Now let's look at something a bit more complex. What should we expect to happen when I change the input to a [[WikiPedia:Square_wave|square wave]]? | ||

let's look at something a bit more complex. What should we expect to | |||

happen when I change the input to a [[WikiPedia:Square_wave|square wave]] | |||

The input scope confirms a 1kHz square wave. The output scope shows... exactly what it should. | |||

What is a square wave really? | What is a square wave really? | ||

We can say it's a waveform that's some positive value for half a cycle and then transitions instantaneously to a negative value for the other half. | |||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\ | \ squarewave(t) = \begin{cases} 1, & |t| < T_1 \\ 0, & T_1 < |t| \leq {1 \over 2}T \end{cases} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

But that doesn't really tell us anything useful about how that input becomes this output. | But that doesn't really tell us anything useful about how that input becomes this output. | ||

We remember that any waveform is also [[WikiPedia:Fourier_series|the sum of discrete frequencies]], | |||

and a square wave is particularly simple sum: a fundamental and an | and a square wave is particularly simple sum: a fundamental and an infinite series of [[WikiPedia:Even_and_odd_functions#Harmonics|odd harmonics]]. | ||

infinite series of [[WikiPedia:Even_and_odd_functions#Harmonics|odd harmonics]] | |||

[[ | [[image:Dsat_013.jpg|360px|right]] | ||

:<math>\begin{align} | :<math>\begin{align} | ||

\ squarewave(t) = \frac{4}{\pi}\sin(\omega t) + \frac{4}{3\pi}\sin(3\omega t) + \frac{4}{5\pi}\sin(5\omega t) + \\ | |||

\frac{4}{7\pi}\sin(7\omega t) + \frac{4}{9\pi}\sin(9\omega t) + \frac{4}{11\pi}\sin(11\omega t) + \\ | \frac{4}{7\pi}\sin(7\omega t) + \frac{4}{9\pi}\sin(9\omega t) + \frac{4}{11\pi}\sin(11\omega t) + \\ | ||

\frac{4}{13\pi}\sin(13\omega t) + \frac{4}{15\pi}\sin(15\omega t) + \frac{4}{17\pi}\sin(17\omega t) + \\ | \frac{4}{13\pi}\sin(13\omega t) + \frac{4}{15\pi}\sin(15\omega t) + \frac{4}{17\pi}\sin(17\omega t) + \\ | ||

| Line 380: | Line 314: | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

At first glance, that doesn't seem very useful either | At first glance, that doesn't seem very useful either; you'd have to sum an infinite number of harmonics to get the answer! However, we don't have an infinite number of harmonics. | ||

We're using a quite sharp [[WikiPedia:Low-pass_filter|anti-aliasing filter]] that cuts off right | We're using a quite sharp [[WikiPedia:Low-pass_filter|anti-aliasing filter]] that cuts off right | ||

above 20kHz, so our signal is [[WikiPedia:Bandlimiting|bandlimited]] | above 20kHz, so our signal is [[WikiPedia:Bandlimiting|bandlimited]]. Only the first ten terms make it through, and that's exactly what we see on the output scope. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

<center><div style="background-color:#DDDDFF;border-color:#CCCCDD;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | <center><div style="background-color:#DDDDFF;border-color:#CCCCDD;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | ||

'''Going deeper…''' | '''Going deeper…''' | ||

*In modern web browsers you can program audio synthesizers directly in javascript. Use the two square wave formulas to get a square wave out of [http://js.do/blog/sound-waves-with-javascript/ this page]. (Note: The scope is not very useful.) | *In modern web browsers you can program audio synthesizers directly in javascript. Use the two square wave formulas to get a square wave out of [http://js.do/blog/sound-waves-with-javascript/ this page]. (Note: The scope is not very accurate/useful.) | ||

</div></center> | </div></center> | ||

<div> </div> | |||

The rippling you see around sharp edges in a bandlimited signal is called the [[WikiPedia: | [[Image:dsat_015.jpg|360px|right]] | ||

The rippling you see around sharp edges in a bandlimited signal is called the [[WikiPedia:Gibbs phenomenon|Gibbs effect]]. It happens whenever you slice off part of the frequency domain in the middle of nonzero energy. | |||

The usual rule of thumb you'll hear is "the sharper the cutoff, the | The usual rule of thumb you'll hear is "the sharper the cutoff, the | ||

stronger the rippling", which is approximately true, but we have to be | stronger the rippling", which is approximately true, but we have to be | ||

careful how we think about it. | careful how we think about it. For example, what would you expect our quite sharp anti-aliasing filter | ||

For example | |||

to do if I run our signal through it a second time? | to do if I run our signal through it a second time? | ||

Aside from adding a few fractional cycles of delay, the answer is | Aside from adding a few fractional cycles of delay, the answer is: | ||

Nothing at all. The signal is already bandlimited. Bandlimiting it | |||

again doesn't do anything. A second pass can't remove frequencies | again doesn't do anything. A second pass can't remove frequencies | ||

that we already removed. | that we already removed. | ||

That's important. People tend to think of the ripples as | |||

a kind of [[WikiPedia:Sonic_artifact|artifact]] that's added by anti-aliasing and [[WikiPedia:Reconstruction_filter|anti-imaging]] | a kind of [[WikiPedia:Sonic_artifact|artifact]] that's added by anti-aliasing and [[WikiPedia:Reconstruction_filter|anti-imaging]] | ||

filters, implying that the ripples get worse each time the signal | filters, implying that the ripples get worse each time the signal | ||

passes through. We | passes through. We see that in this case that didn't happen, so | ||

it wasn't really the filter that added the ripples the first time | |||

through | through. It's a subtle distinction, but Gibbs effect | ||

ripples aren't added by filters, they're just part of what a | ripples aren't added by filters, they're just part of what a | ||

bandlimited signal ''is''. | bandlimited signal ''is''. | ||

Even if we synthetically construct what looks like a perfect digital | Even if we synthetically construct what looks like a perfect digital | ||

square wave | square wave it's still limited to the channel bandwidth. Remember that | ||

the stairstep representation is misleading. What we really have here are instantaneous sample points | |||

it's still limited to the channel bandwidth. Remember | |||

the stairstep representation is misleading. | |||

What we really have here are instantaneous sample points | |||

and only one bandlimited signal fits those points. All we did when we | and only one bandlimited signal fits those points. All we did when we | ||

drew our apparently perfect square wave was line up the sample points | drew our apparently perfect square wave was line up the sample points | ||

just right so it appeared that there were no ripples if we played | just right so it appeared that there were no ripples if we played | ||

[[WikiPedia:Interpolation|connect-the-dots]]. | [[WikiPedia:Interpolation|connect-the-dots]]. The original bandlimited signal, complete with ripples, was | ||

still there. | still there. | ||

[[image:Dsat_014.gif|360px|right]] | [[image:Dsat_014.gif|360px|right]] | ||

That leads us to one more important point. You've probably heard | |||

that the timing precision of a digital signal is limited by its sample | that the timing precision of a digital signal is limited by its sample | ||

rate; put another way, | rate; put another way, that digital signals can't represent anything that falls between the | ||

that digital signals can't represent anything that falls between the | |||

samples.. implying that [[WikiPedia:Dirac_delta_function|impulses]] or | samples.. implying that [[WikiPedia:Dirac_delta_function|impulses]] or | ||

[[WikiPedia:Synthesizer#ADSR_envelope|fast attacks]] have to align exactly | [[WikiPedia:Synthesizer#ADSR_envelope|fast attacks]] have to align exactly | ||

with a sample, or the timing gets mangled | with a sample, or the timing gets mangled or they just disappear. | ||

At this point, we can easily see why that's wrong. | At this point, we can easily see why that's wrong. | ||

| Line 454: | Line 377: | ||

[[Image:Moffey.jpg|360px|right]] | [[Image:Moffey.jpg|360px|right]] | ||

Like in [[Videos/A Digital Media Primer For Geeks|A Digital Media Primer for Geeks]], we've covered a broad range of topics, and yet barely scratched the surface of each one. If anything, my sins of omission are greater this time around. | |||

topics, and yet barely scratched the surface of each one. | |||

sins of omission are greater this time around | |||

Thus I encourage you to dig deeper and experiment. I chose my demos carefully to be simple and give clear results. You can reproduce every one of them on your own if you like, but let's face it: sometimes we learn the most about a spiffy toy by breaking it open and studying all the pieces that fall out. Play with the demo parameters, hack up the code, set up alternate experiments. The [[#Use The Source Luke|source code for everything, including the little push-button demo application]], is at the end of this transcript. | |||

demos | |||

reproduce every one of them on your own if you like | |||

it | |||

and studying all the pieces that fall out. | |||

alternate experiments. | |||

little | |||

In the course of experimentation, you're likely to run into something | In the course of experimentation, you're likely to run into something that you didn't expect and can't explain. Don't worry! My earlier snark aside, Wikipedia is fantastic for exactly this kind of casual research. If you're really serious about understanding signals, several universities have advanced materials online, such as the [http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/electrical-engineering-and-computer-science/6-003-signals-and-systems-fall-2011/ 6.003] and [http://ocw.mit.edu/resources/res-6-007-signals-and-systems-spring-2011/ RES.6-007] Signals and Systems modules at MIT OpenCourseWare. And, of course, there's always the [http://webchat.freenode.net/?channels=xiph community here at Xiph.Org]. | ||

that you didn't expect and can't explain. | |||

snark aside, Wikipedia is fantastic for exactly this kind of casual | |||

research. | |||

several universities have advanced materials online, such as the | |||

[http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/electrical-engineering-and-computer-science/6-003-signals-and-systems- | |||

and | |||

[http://ocw.mit.edu/resources/res-6-007-signals-and-systems-spring-2011/ RES.6-007] | |||

Signals and Systems modules at MIT OpenCourseWare. And of | |||

course, there's always the [http://webchat.freenode.net/?channels=xiph community here at Xiph.Org]. | |||

==Credits== | ==Credits== | ||

| Line 514: | Line 415: | ||

A Co-Production of Xiph.Org and Red Hat, Inc.<br> | A Co-Production of Xiph.Org and Red Hat, Inc.<br> | ||

(C) 2012-2013, Some Rights Reserved<br> | (C) 2012-2013, Some Rights Reserved<br> | ||

<hr/> | |||

== Use The Source Luke == | == Use The Source Luke == | ||

As stated in the Epilogue, everything that appears in the video demos is driven by open source software, which means the source is both available for inspection and freely usable by the community. The Thinkpad that appears in the video was running Fedora 17 and Gnome Shell (Gnome 3). The demonstration software does not require Fedora specifically, but it does require Gnu/Linux to run in its current form. In all, the video involved just under 50,000 lines of new and custom-purpose code (including contributions to non-Xiph projects such as Cinelerra and Gromit). | As stated in the Epilogue, everything that appears in the video demos is driven by open source software, which means the source is both available for inspection and freely usable by the community. The Thinkpad that appears in the video was running Fedora 17 and Gnome Shell (Gnome 3). The demonstration software does not require Fedora specifically, but it does require Gnu/Linux to run in its current form. In all, the video involved just under 50,000 lines of new and custom-purpose code (including contributions to non-Xiph projects such as Cinelerra and [http://sourceforge.net/projects/gromit-mpx/ Gromit]). | ||

=== The Spectrum and Waveform Viewer === | === The Spectrum and Waveform Viewer === | ||

| Line 538: | Line 440: | ||

The touch-controlled application used in the video is named 'gtk-bounce' and was custom-written for the sole purpose of the in-video demonstrations. It is so named because, for the most part, all it does is read the input from an audio device, and then immediately write the same data back out for playback. It also forwards a copy of this data to up to two external monitoring applications, and in several demos, applies simple filters or generates simple waveforms. It includes several demos not included in the video. | The touch-controlled application used in the video is named 'gtk-bounce' and was custom-written for the sole purpose of the in-video demonstrations. It is so named because, for the most part, all it does is read the input from an audio device, and then immediately write the same data back out for playback. It also forwards a copy of this data to up to two external monitoring applications, and in several demos, applies simple filters or generates simple waveforms. It includes several demos not included in the video. | ||

<center><div style="background-color:# | <center><div style="background-color:#DDDDDD;border-color:#CCCCCC;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | ||

*Source for gtk-bounce is found at: | *Source for gtk-bounce is found at: | ||

https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/ | https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/ | ||

| Line 544: | Line 446: | ||

svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/ | svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/ | ||

*Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy: | *Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy: | ||

https://trac.xiph.org/browser/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/ | https://trac.xiph.org/browser/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/ | ||

</div></center> | </div></center> | ||

| Line 551: | Line 453: | ||

Assuming gtk-bounce, spectrum and waveform have been checked out and built, the configuration seen in the video can be started using the following commands: | Assuming gtk-bounce, spectrum and waveform have been checked out and built, the configuration seen in the video can be started using the following commands: | ||

<center><div style="background-color:# | <center><div style="background-color:#DDDDDD;border-color:#CCCCCC;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | ||

* make the pipe fifos for the applications to communicate (only needs to be done once) | * make the pipe fifos for the applications to communicate (only needs to be done once) | ||

mkfifo pipe0 pipe1 | mkfifo pipe0 pipe1 | ||

| Line 560: | Line 462: | ||

==== Using Gtk-bounce ==== | ==== Using Gtk-bounce ==== | ||

Gtk-bounce consists of eleven pushbutton panels (numbered zero through ten) that can be selected by scrolling up and | Gtk-bounce consists of eleven pushbutton panels (numbered zero through ten) that can be selected by scrolling up and down with the arrow buttons on the right side. Each panel is intended for a specific demo or part of a demo. | ||

<center><div style="background-color:# | <center><div style="background-color:#DDDDDD;border-color:#CCCCCC;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | ||

[[Image:Dsat-panel0.png|700px|center]] | [[Image:Dsat-panel0.png|700px|center]] | ||

| Line 589: | Line 491: | ||

[[Image:Dsat-panel6.png|700px|center]] | [[Image:Dsat-panel6.png|700px|center]] | ||

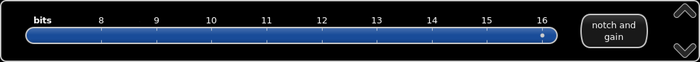

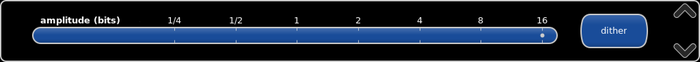

* '''Panel 6''': allows the user to play with the power of the dithering noise applied before | * '''Panel 6''': allows the user to play with the power of the dithering noise applied before quantizing the sine wave. Shaped or flat dither are available. The sine wave may also be modulated with a varying amplitude to highlight correlations between the input and the resulting quantization noise. The 'notch and gain' button applies a notch filter to the resulting signal, and boosts the gain of the remaining noise so that it's easily audible. The audio input from the audio device is discarded. | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

[[Image:Dsat-panel7.png|700px|center]] | [[Image:Dsat-panel7.png|700px|center]] | ||

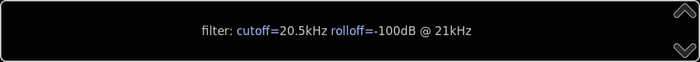

* '''Panel 7''': applies a sharper antialiasing (lowpass) filter than is likely to be built into the sound-card hardware (as there's generally no reason to use a filter quite this sharp in practice). The very sharp filter allows us to bandpass the demonstration | * '''Panel 7''': applies a sharper antialiasing (lowpass) filter than is likely to be built into the sound-card hardware (as there's generally no reason to use a filter quite this sharp in practice). The very sharp filter allows us to bandpass the demonstration square wave without any harmonics landing in the transition band. The input is read from the audio device, passed through this sharper filter, and then forwarded to the outputs. | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

[[Image:Dsat-panel8.png|700px|center]] | [[Image:Dsat-panel8.png|700px|center]] | ||

* '''Panel 8''': when selected, generate a synthetic ' | * '''Panel 8''': when selected, generate a synthetic 'square wave' (this is not quite equivalent to a bandlimited analog square wave; the harmonic amplitudes are a bit different) that when aligned with the sampling phase just right gives the appearance of having infinite rise and fall time. The slider allows us to shift the waveform sample alignment back and forth by +/- one sample to reveal that the underlying signal is still band-limited. | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

[[Image:Dsat-panel9.png|700px|center]] | [[Image:Dsat-panel9.png|700px|center]] | ||

* '''Panel 9''': | * '''Panel 9''': as in panel 8, generate a 'perfect' synthetic 'square wave'. However, the slider now allows us to shift the sample alignment of the second channel with respect to the first, instead of shifting both channels. This allows us the trigger/lock the scope timing to the channel 1 waveform so we can see the fractional sample movement and alignment of the waveform on channel 2. The audio input from the audio device is discarded. | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

[[Image:Dsat-panel10.png|700px|center]] | [[Image:Dsat-panel10.png|700px|center]] | ||

* '''Panel 10''': | * '''Panel 10''': not used in the video; The audio device is configured to 24-bit input/output. The user may produce one of a range of test signals that are output to both the external applications and the audio device on the first channel. The input on the second channel is passed-through to the applications and audio device outputs unchanged. The first channel input is unused unless 'two input mode' is selected. When two input mode is selected, both input channels are read and the data sent to the external applications. Generated test signals are sent only to the audio hardware (on the first channel). This combination of test signals and input modes allows self-references frequency response, phase, noise, distortion and crosstalk testing of a given audio device. | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

| Line 614: | Line 517: | ||

The animations featured throughout the Episode 2 video were rapid-development spaghetti hack-jobs coded by hand in raw Cairo. Each module generated a series of PNG stills that were then stitched into an animation with Cinelerra or mplayer. In the interest of pointing and laughing at what really bad code looks like... | The animations featured throughout the Episode 2 video were rapid-development spaghetti hack-jobs coded by hand in raw Cairo. Each module generated a series of PNG stills that were then stitched into an animation with Cinelerra or mplayer. In the interest of pointing and laughing at what really bad code looks like... | ||

<center><div style="background-color:# | <center><div style="background-color:#DDDDDD;border-color:#CCCCCC;border-style:solid;width:80%;padding:0 1em 1em 1em;text-align:left;"> | ||

*Source for the Cairo animations is found at: | *Source for the Cairo animations is found at: | ||

https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/ | https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/ | ||

| Line 620: | Line 523: | ||

svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/ | svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/ | ||

*Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy: | *Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy: | ||

https://trac.xiph.org/browser/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/ | https://trac.xiph.org/browser/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/ | ||

</div></center> | </div></center> | ||

Latest revision as of 09:19, 2 July 2013

Wiki edition

Continuing in the "firehose" tradition of Episode 01, Xiph.Org's second video on digital media explores multiple facets of digital audio signals and how they really behave in the real world.

Demonstrations of sampling, quantization, bit-depth, and dither explore digital audio behavior on real audio equipment using both modern digital analysis and vintage analog bench equipment, just in case we can't trust those newfangled digital gizmos. You can download the source code for each demo and try it all for yourself!

Supported players: VLC 1.1+, Firefox , Chrome , Opera. Or see other WebM or other Theora players.

If you're having trouble with playback in a modern browser or player, please visit our playback troubleshooting and discussion page.

“Hi, I'm Monty Montgomery from Red Hat and Xiph.Org.

“A few months ago, I wrote an article on digital audio and why 24bit/192kHz music downloads don't make sense. In the article, I mentioned--almost in passing--that a digital waveform is not a stairstep, and you certainly don't get a stairstep when you convert from digital back to analog.

“Of everything in the entire article, that was the number one thing people wrote about. In fact, more than half the mail I got was questions and comments about basic digital signal behavior. Since there's interest, let's take a little time to play with some simple digital signals. ”

Veritas ex machina

If we pretend for a moment that we have no idea how digital signals really behave, then it doesn't make sense for us to use digital test equipment. Fortunately for this exercise, there's still plenty of working analog lab equipment out there.

We need a signal generator to provide us with analog input signals--in this case, an HP3325 from 1978.

We'll observe our analog waveforms on analog oscilloscopes, like this Tektronix 2246 from the mid-90s, one of the last and best analog scopes made.

Finally, we'll inspect the frequency spectrum of our signals using an analog spectrum analyzer, this HP3585 from the same product line as the signal generator. Like the other equipment here it has a rudimentary and hilariously large microcontroller, but the signal path from input to what you see on the screen is completely analog.

All of this equipment is vintage, but the specs are still quite good. We start with the signal generator set to output a 1 kHz sine wave at one Volt RMS. We see the sine wave on the oscilloscope, can verify that it is indeed 1 kHz at 1 Volt RMS, which is 2.8 Volts peak-to-peak, and that matches the measurement on the spectrum analyzer as well.

The analyzer also shows some low-level white noise and just a bit of harmonic distortion, with the highest peak about 70dB or so below the fundamental. This doesn't matter to the demos, but it's good to take notice of it now to avoid confusion later.

For digital conversion, we use a boring, consumer-grade, eMagic USB1 audio device. It's more than ten years old at this point, and it's getting obsolete.

A recent converter can easily have an order of magnitude better specs. Flatness, linearity, jitter, noise behavior, everything... You may not have noticed. Just because we can measure an improvement doesn't mean we can hear it, and even these old consumer boxes were already at the edge of ideal transparency.

The eMagic connects to my ThinkPad, which displays a digital waveform and spectrum for comparison, then the ThinkPad sends the digital signal right back out to the eMagic for re-conversion to analog and observation on the output scopes.

Stairsteps

First demo: We begin by converting an analog signal to digital and then right back to analog again with no other steps.

The signal generator is set to produce a 1kHz sine wave just like before and we can see the analog sine wave on the input-side oscilloscope. The eMagic digitizes our signal to 16 bit PCM at 44.1kHz, same as on a CD. The spectrum of the digitized signal on the Thinkpad matches what we saw earlier and what we see now on the analog spectrum analyzer, aside from its high-impedance input being just a smidge noisier. For now, the waveform display shows our digitized sine wave as a stairstep pattern, one step for each sample.

When we look at the output signal that's been converted from digital back to analog, we see that it's exactly like the original sine wave. No stairsteps.

1 kHz is still a fairly low frequency, so perhaps the stairsteps are just hard to see or they're being smoothed away. Next, set the signal generator to 15kHz, which is much closer to Nyquist. Now the sine wave is represented by less than three samples per cycle, and the digital waveform appears rather poor! Yet the analog output is still a perfect sine wave, exactly like the original. As we keep increasing frequency, all the way to 20kHz, the output waveform is still perfect. No jagged edges, no dropoff, no stairsteps.

So where'd the stairsteps go? It's a trick question; they were never there. Drawing a digital waveform as a stairstep was wrong to begin with.

A stairstep is a continuous-time function. It's jagged, and it's piecewise, but it has a defined value at every point in time. A sampled signal is entirely different. It's discrete-time; it's only got a value right at each instantaneous sample point and it's undefined, there is no value at all, everywhere between. A discrete-time signal is properly drawn as a lollipop graph. The continuous, analog counterpart of a digital signal passes smoothly through each sample point, and that's just as true for high frequencies as it is for low.

The interesting and non-obvious bit is that there's only one bandlimited signal that passes exactly through each sample point; it's a unique solution. If you sample a bandlimited signal and then convert it back, the original input is also the only possible output. A signal that differs even minutely from the original includes frequency content at or beyond Nyquist, breaks the bandlimiting requirement and isn't a valid solution.

So how did everyone get confused and start thinking of digital signals as stairsteps? I can think of two good reasons.

First: it's easy to convert a sampled signal to a true stairstep. Just extend each sample value forward until the next sample period. This is called a zero-order hold, and it's an important part of how some digital-to-analog converters work, especially the simplest ones. As a result, anyone who looks up digital-to-analog converter or digital-to-analog conversion is probably going to see a diagram of a stairstep waveform somewhere, but that's not a finished conversion, and it's not the signal that comes out.

Second, and this is probably the more likely reason, engineers who supposedly know better (yes, even I) draw stairsteps even though they're technically wrong. It's a sort of one-dimensional version of fat bits in an image editor. Pixels aren't squares either, they're samples of a 2-dimensional function space and so they're also, conceptually, infinitely small points. Practically, it's a real pain in the ass to see or manipulate infinitely small anything, so big squares it is.

Digital stairstep drawings are exactly the same thing. It's just a convenient drawing. The stairsteps aren't really there.

Bit-depth

When we convert a digital signal back to analog, the result is also smooth regardless of the bit depth. It doesn't matter if it's 24 bits or 16 bits or 8 bits. So does that mean that the digital bit depth makes no difference at all? Of course not.

Channel 2 is the same sine wave input, but we quantize it with dither down to 8 bits. On the scope, we still see a nice smooth sine wave on channel 2. Look very close, and you'll also see a bit more noise. That's a clue.

If we look at the spectrum of the signal, our sine wave is still there unaffected, but the noise level of the 8-bit signal on the second channel is much higher. And that's the difference, the only difference, the number of bits makes.

When we digitize a signal, first we sample it. The sampling step is perfect; it loses nothing. But then we quantize it, and quantization adds noise. The number of bits determines how much noise and so the level of the noise floor.

What does this dithered quantization noise sound like? Those of you who have used analog recording equipment might think to yourselves, "My goodness! That sounds like tape hiss!" Well, it doesn't just sound like tape hiss, it acts like it too, and if we use a gaussian dither then it's mathematically equivalent in every way. It is tape hiss.

Intuitively, that means that we can measure tape hiss and thus the noise floor of magnetic audio tape in bits instead of decibels, in order to put things in a digital perspective. Compact cassettes, for those of you who are old enough to remember them, could reach as deep as 9 bits in perfect conditions. 5 to 6 bits was more typical, especially if it was a recording made on a tape deck. That's right; your old mix tapes were only about 6 bits deep if you were lucky!

The very best professional open reel tape used in studios could barely hit 13 bits with advanced noise reduction. That's why seeing 'D D D' on a Compact Disc used to be such a big, high-end deal.

Dither

We've been quantizing with dither. What is dither exactly and, more importantly, what does it do?

The simplest way to quantize a signal is to choose the digital

amplitude value closest to the original analog amplitude.

Unfortunately, the exact noise that results from this simple

quantization scheme depends somewhat on the input signal.

It may be inconsistent, cause distortion, or be

undesirable in some other way.

Going deeper…

- Cameron Nicklaus Christou's thesis Optimal Dither and Noise Shaping in Image Processing provides an excellent explanation of dither and noise shaping.

Dither is specially-constructed noise that substitutes for the noise produced by simple quantization. Dither doesn't drown out or mask quantization noise, it replaces it with noise characteristics of our choosing that aren't influenced by the input.

The signal generator has too much noise for this test so we produce a mathematically perfect sine wave with the ThinkPad and quantize it to 8 bits with dithering. We see the sine wave on waveform display and output scope, and a clean frequency peak with a uniform noise floor on both spectral displays just like before. Again, this is with dither.

Now I turn dithering off.

The quantization noise that dither had spread out into a nice, flat noise floor, piles up into harmonic distortion peaks. The noise floor is lower, but the level of distortion becomes nonzero, and the distortion peaks sit higher than the dithering noise did.

At 8 bits this effect is exaggerated. At 16 bits, even without dither, harmonic distortion is going to be so low as to be completely inaudible. Still, we can use dither to eliminate it completely if we so choose.

Turning the dither off again for a moment, you'll notice that the absolute level of distortion from undithered quantization stays approximately constant regardless of the input amplitude. But when the signal level drops below a half a bit, everything quantizes to zero.

In a sense, everything quantizing to zero is just 100% distortion! Dither eliminates this distortion too. When we reenable dither, we clearly see our signal at 1/4 bit with a nice flat noise floor.

The noise floor doesn't have to be flat. Dither is noise of our choosing, so it makes sense to choose a noise as inoffensive and difficult to notice as possible.

Human hearing is most sensitive in the midrange from 2kHz to 4kHz; that's where background noise is going to be the most obvious. We can shape dithering noise away from sensitive frequencies to where hearing is less sensitive, usually the highest frequencies.

Lastly, dithered quantization noise is higher power overall than undithered quantization noise, even though it often sounds quieter, and you can see that on a VU meter during passages of near-silence. However, dither isn't only an on or off choice. We can reduce the dither's power to balance less noise against a bit of distortion to minimize the overall effect.

For the next test, we also modulate the input signal like this to show how a varying input affects the quantization noise. At full dithering power, the noise is uniform, constant, and featureless just like we expect.

As we reduce the dither's power, the input increasingly affects the amplitude and the character of the quantization noise. Shaped dither behaves similarly, but noise shaping lends one more nice advantage; it can use a somewhat lower dither power before the input has as much effect on the output.

Despite all this text spent on dither, the differences exist 100 decibels or more below full scale. If the CD had been 14 bits as originally designed, perhaps dither might be more important. At 16 bits it's mostly a wash. It's reasonable to treat dither as an insurance policy that gives several extra decibels of dynamic range just in case. That said no one ever ruined a great recording by not dithering the final master.

Bandlimitation and timing

We've been using sine waves. They're the obvious choice when what we want to see is a system's behavior at a given isolated frequency. Now let's look at something a bit more complex. What should we expect to happen when I change the input to a square wave?

The input scope confirms a 1kHz square wave. The output scope shows... exactly what it should.

What is a square wave really?

We can say it's a waveform that's some positive value for half a cycle and then transitions instantaneously to a negative value for the other half.

But that doesn't really tell us anything useful about how that input becomes this output.

We remember that any waveform is also the sum of discrete frequencies, and a square wave is particularly simple sum: a fundamental and an infinite series of odd harmonics.

At first glance, that doesn't seem very useful either; you'd have to sum an infinite number of harmonics to get the answer! However, we don't have an infinite number of harmonics.

We're using a quite sharp anti-aliasing filter that cuts off right above 20kHz, so our signal is bandlimited. Only the first ten terms make it through, and that's exactly what we see on the output scope.

Going deeper…

- In modern web browsers you can program audio synthesizers directly in javascript. Use the two square wave formulas to get a square wave out of this page. (Note: The scope is not very accurate/useful.)

The rippling you see around sharp edges in a bandlimited signal is called the Gibbs effect. It happens whenever you slice off part of the frequency domain in the middle of nonzero energy.

The usual rule of thumb you'll hear is "the sharper the cutoff, the stronger the rippling", which is approximately true, but we have to be careful how we think about it. For example, what would you expect our quite sharp anti-aliasing filter to do if I run our signal through it a second time?

Aside from adding a few fractional cycles of delay, the answer is: Nothing at all. The signal is already bandlimited. Bandlimiting it again doesn't do anything. A second pass can't remove frequencies that we already removed.

That's important. People tend to think of the ripples as a kind of artifact that's added by anti-aliasing and anti-imaging filters, implying that the ripples get worse each time the signal passes through. We see that in this case that didn't happen, so it wasn't really the filter that added the ripples the first time through. It's a subtle distinction, but Gibbs effect ripples aren't added by filters, they're just part of what a bandlimited signal is.

Even if we synthetically construct what looks like a perfect digital square wave it's still limited to the channel bandwidth. Remember that the stairstep representation is misleading. What we really have here are instantaneous sample points and only one bandlimited signal fits those points. All we did when we drew our apparently perfect square wave was line up the sample points just right so it appeared that there were no ripples if we played connect-the-dots. The original bandlimited signal, complete with ripples, was still there.

That leads us to one more important point. You've probably heard that the timing precision of a digital signal is limited by its sample rate; put another way, that digital signals can't represent anything that falls between the samples.. implying that impulses or fast attacks have to align exactly with a sample, or the timing gets mangled or they just disappear. At this point, we can easily see why that's wrong.

Again, our input signals are bandlimited. And digital signals are samples, not stairsteps, not 'connect-the-dots'. We most certainly can, for example, put the rising edge of our bandlimited square wave anywhere we want between samples.

It's represented perfectly and it's reconstructed perfectly.

Epilogue

Like in A Digital Media Primer for Geeks, we've covered a broad range of topics, and yet barely scratched the surface of each one. If anything, my sins of omission are greater this time around.

Thus I encourage you to dig deeper and experiment. I chose my demos carefully to be simple and give clear results. You can reproduce every one of them on your own if you like, but let's face it: sometimes we learn the most about a spiffy toy by breaking it open and studying all the pieces that fall out. Play with the demo parameters, hack up the code, set up alternate experiments. The source code for everything, including the little push-button demo application, is at the end of this transcript.

In the course of experimentation, you're likely to run into something that you didn't expect and can't explain. Don't worry! My earlier snark aside, Wikipedia is fantastic for exactly this kind of casual research. If you're really serious about understanding signals, several universities have advanced materials online, such as the 6.003 and RES.6-007 Signals and Systems modules at MIT OpenCourseWare. And, of course, there's always the community here at Xiph.Org.

Credits

Written by: Christopher (Monty) Montgomery and the Xiph.Org Community

Special thanks to:

- Heidi Baumgartner, for the second Tektronix oscilloscope

- Gregory Maxwell and Dr. Timothy Terriberry, for additional technical review

Intro, title and credits music:

"Andy Warhol Is Gone", by Lousy Robot

Used by permission of Lousy Robot.

Original source track All Rights Reserved.

www.lousyrobot.com

This Video Was Produced Entirely With Free and Open Source Software:

All trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

A Co-Production of Xiph.Org and Red Hat, Inc.

(C) 2012-2013, Some Rights Reserved

Use The Source Luke

As stated in the Epilogue, everything that appears in the video demos is driven by open source software, which means the source is both available for inspection and freely usable by the community. The Thinkpad that appears in the video was running Fedora 17 and Gnome Shell (Gnome 3). The demonstration software does not require Fedora specifically, but it does require Gnu/Linux to run in its current form. In all, the video involved just under 50,000 lines of new and custom-purpose code (including contributions to non-Xiph projects such as Cinelerra and Gromit).

The Spectrum and Waveform Viewer

The realtime software spectrum analyzer application that appears in the video was a preexisting application that was dusted off and updated for use in the video. The waveform viewer (effectively a simple software oscilloscope) was written from scratch making use of some of the internals from the spectrum analyzer application. Both are available from Xiph.Org svn:

- Source for the Spectrum and Waveform applications is found at:

https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/spectrum/

- The source can be checked out of svn using the following command line:

svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/spectrum

- Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy:

Spectrum and Waveform both expect an input stream on the command line, either as raw data or as a WAV file.

GTK-Bounce

The touch-controlled application used in the video is named 'gtk-bounce' and was custom-written for the sole purpose of the in-video demonstrations. It is so named because, for the most part, all it does is read the input from an audio device, and then immediately write the same data back out for playback. It also forwards a copy of this data to up to two external monitoring applications, and in several demos, applies simple filters or generates simple waveforms. It includes several demos not included in the video.

- Source for gtk-bounce is found at:

https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/

- The source can be checked out of svn using the following command line:

svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/bounce/

- Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy:

Starting Gtk-bounce

The application is somewhat hardwired for specific demo parameters, but most of the hardwired settings can be found at the top of each source file. As found in SVN, the application expects an ALSA hardware audio device at hw:1, and if none if found, it will wait for one to appear. Once a sound device is successfully initialized, it expects to find and open two pipes named pipe0 and pipe1 for output in the current directory. In the video, the waveform and spectrum applications are started to take input from pipe0 and pipe1 respectively. The output sent to the two pipes is identical, and in most demos matches the output data sent to the hardware device for conversion to analog. The only exception is the tenth demo panel (which does not appear in the video) where gtk-bounce can be set to monitor the hardware inputs instead while the outputs are used to produce test waveforms.

Assuming gtk-bounce, spectrum and waveform have been checked out and built, the configuration seen in the video can be started using the following commands:

- make the pipe fifos for the applications to communicate (only needs to be done once)

mkfifo pipe0 pipe1

- start all three applications

waveform pipe0 & spectrum pipe1 & gtk-bounce &

Using Gtk-bounce

Gtk-bounce consists of eleven pushbutton panels (numbered zero through ten) that can be selected by scrolling up and down with the arrow buttons on the right side. Each panel is intended for a specific demo or part of a demo.

- Panel 0: This panel presents buttons that allow the sound card to be configured in several sampling rates and bit depths. Samples read from the audio inputs are sent to the output pipes and audio outputs for playback without modification.

- Panel 1: Both channels are forwarded to the outputs, however the user may select the bit depth of each channel independently. When the sound card is running in 16 bit mode and 16-bit depth is selected, the data is untouched. Requantization to a lower bit depth is performed with a flat triangle dither.

- Panel 2: Both channels are re-quantized to the selected bit depth. Requantization to a lower bit depth is performed with a flat triangle dither.

- Panel 3: 'generate sine wave' discards the audio inputs and instead internally generates a sine wave at 32 bit precision, which is then quantized to the selected bit depth, optionally with dither. The resulting signal is then forwarded to the output.

- Panel 4: gtk-bounce generates a 16-bit sine wave of the selected amplitude, optionally with dither, and forwards the resulting signal to the outputs. The audio input from the audio device is discarded. Note that the slider sets the peak amplitude, not the peak-to-peak amplitude.

- Panel 5: generates a 16-bit sine wave, optionally quantized using dither. The user may additionally select a flat or a shaped dither. The 'notch and gain' button applies a notch filter to the resulting signal, and boosts the gain of the remaining noise so that it's easily audible. The audio input from the audio device is discarded.

- Panel 6: allows the user to play with the power of the dithering noise applied before quantizing the sine wave. Shaped or flat dither are available. The sine wave may also be modulated with a varying amplitude to highlight correlations between the input and the resulting quantization noise. The 'notch and gain' button applies a notch filter to the resulting signal, and boosts the gain of the remaining noise so that it's easily audible. The audio input from the audio device is discarded.

- Panel 7: applies a sharper antialiasing (lowpass) filter than is likely to be built into the sound-card hardware (as there's generally no reason to use a filter quite this sharp in practice). The very sharp filter allows us to bandpass the demonstration square wave without any harmonics landing in the transition band. The input is read from the audio device, passed through this sharper filter, and then forwarded to the outputs.

- Panel 8: when selected, generate a synthetic 'square wave' (this is not quite equivalent to a bandlimited analog square wave; the harmonic amplitudes are a bit different) that when aligned with the sampling phase just right gives the appearance of having infinite rise and fall time. The slider allows us to shift the waveform sample alignment back and forth by +/- one sample to reveal that the underlying signal is still band-limited.

- Panel 9: as in panel 8, generate a 'perfect' synthetic 'square wave'. However, the slider now allows us to shift the sample alignment of the second channel with respect to the first, instead of shifting both channels. This allows us the trigger/lock the scope timing to the channel 1 waveform so we can see the fractional sample movement and alignment of the waveform on channel 2. The audio input from the audio device is discarded.

- Panel 10: not used in the video; The audio device is configured to 24-bit input/output. The user may produce one of a range of test signals that are output to both the external applications and the audio device on the first channel. The input on the second channel is passed-through to the applications and audio device outputs unchanged. The first channel input is unused unless 'two input mode' is selected. When two input mode is selected, both input channels are read and the data sent to the external applications. Generated test signals are sent only to the audio hardware (on the first channel). This combination of test signals and input modes allows self-references frequency response, phase, noise, distortion and crosstalk testing of a given audio device.

Cairo Animations

The animations featured throughout the Episode 2 video were rapid-development spaghetti hack-jobs coded by hand in raw Cairo. Each module generated a series of PNG stills that were then stitched into an animation with Cinelerra or mplayer. In the interest of pointing and laughing at what really bad code looks like...

- Source for the Cairo animations is found at:

https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/

- The source can be checked out of svn using the following command line:

svn co https://svn.xiph.org/trunk/Xiph-episode-II/cairo/

- Trac is a convenient way to browse the source without checking out a copy: